The Western Front

In contrast to the well documented exploits of the 1st and 2nd Battalions, it is much more difficult to produce an ordered account of the exploits of those B.W.I.R. Battalions that served in a labour capacity on the Western Front. Technically speaking, the units were never officially designated labour units as the BWIR was established as an infantry regiment. Some battalions appeared to have been armed accordingly, even when primarily serving in a labour capacity.

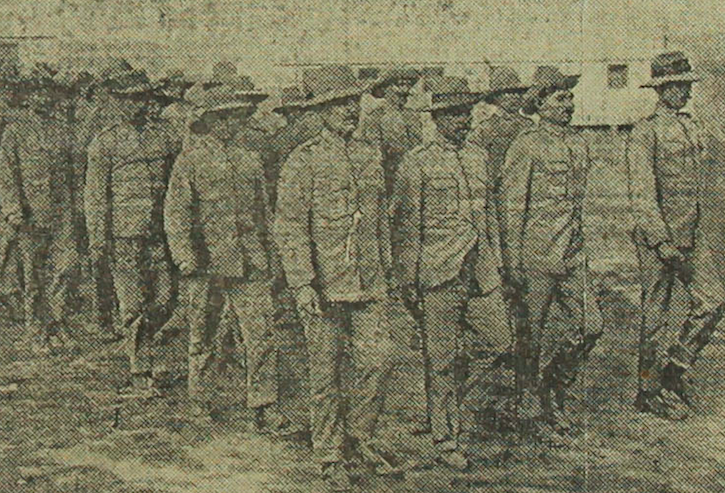

Corporal William Dale of the 10th battalion, for example, described his armaments as a Lee Enfield rifle with a bayonet and shoulder strap, a dagger and a buttoned holster with a Wembley revolver. Official photographs show West Indian troops cleaning their rifles. On the Western Front, the Battalions were primarily involved in manning ammunition dumps, loading and unloading supplies and ammunition at railheads, and moving shells at battery emplacements. These positions were, of course, particularly dangerous for the men because they were constantly at risk of enemy attack, as the Germans wished to destroy reserves of ammunition, break up the railways to hinder or halt allied supply lines and destroy artillery. As such, most of their work was carried out under heavy fire and they endured casualties as a result. Sir Etienne Dupuch O.B.E., later the editor of the Nassau Tribune and a member of the Bahamian House of Assembly, wrote about his First World War experiences at Passchendaele Ridge: “We were taken there to expedite the delivery of shells to the heavy artillery. Our location was a real danger spot. We lost a lot of men there. The Germans laid down a barrage that covered a wide area.”

A question remains as to whether the B.W.I.R. ever took a more active role on the Western Front. Despite no clear military evidence that they were ever used in combat, George Blackman of the 4th Battalion later reported an incident in which he fought in the trenches alongside white soldiers. However, no official record of usage in combat exists.

The B.W.I.R. on the Western Front

The B.W.I.R.’s efforts in the face of such carnage contributed to the Allied action at some of the Western Front’s most iconic battlefields, including the Somme, Ypres, Vimy Ridge, Passchendaele, Arras and Messines. The regiment was also engaged in a variety of other tasks: they dug cable trenches, worked on railways and gun emplacements, moved supplies and those who were armed were assigned to guard duty. All these tasks provided vital support for the front line.

When the Commanding Officers of the 3rd and 4th Battalions, Lieutenant Colonels Barchard and Hart, heard about the conference in Cairo, which resolved that the Regiment would be best used in warmer climates and in a more active role, they wrote a letter to the War Office which rejected the idea that the officers and men of the Battalions were unhappy moving shells and stated that they did not wish to go to Egypt. It is also clear that the men took a certain pride in their work, hence the “King George Steam Engine” moniker that they adopted. This name may have also helped them to distance themselves in some way from other Labour Battalions. Yet this positive attitude appears not to have been shared by all the men. On the 23rd January 1917, the men of the 3rd, who were working on coaling the SS Megantic at Marseilles docks, apparently were a source of some trouble, which resulted in several of them being arrested by the Provost Marshall. This discontent with coaling appears to have continued throughout the month. The reasons for this trouble are unknown. It may be that carrying shells and ammunition may have been more in line with the expectations of volunteers who wished to strike at the enemy, whilst coaling ships may not have had the same appeal.

The 3rd and 4th Battalions were the first contingents to arrive in France at the beginning of September 1916, having come from Egypt which was established as a depot for the BWIR from mid 1916. Upon arrival the battalions were deployed at the Somme, where they were primarily used for moving ammunition. It was partially due to the success of these Battalions in fulfilling their orders that the creation of later Battalions was requested. The 6th Battalion was the first to arrive directly in France in April 1917 and, following a spell of training at Arras, they proceeded to the Ypres Salient. They handled ammunition at dumps, railheads and the batteries in this area during the taking of Puckem Ridge, Poelcappelle and Passchendaele. The 7th Battalion would soon follow, landing at Brest in June 1917. A month later, the 8th arrived and the 9th arrived in August 1917.

The 10th Battalion arrived in France at Le Havre in October 1917 and from there proceeded to St Omer where they were divided into two. A and D Companies went to the Ypres Salient to act as shell carriers for the artillery. It is also attested by Corporal William Dale that they spent time guarding land recaptured from the Germans whilst the allied forces advanced. B and C companies were attached to the Royal Air Force stations near St. Omer until the beginning of January 1918. In January they left for the Taranto base, where they were to spend the rest of the war. The 11th Battalion was sent to work at Taranto as soon as they arrived in Europe.

Many of the Battalions wintered at the Taranto base in Italy during 1917-18, where they engaged in construction work, loaded and unloaded ships and trains and loaded lighters with stores and ammunition for the British forces in the Mediterranean and Middle East. The decision to move them to a warmer area was probably due to the difficulties that the Regiment had faced in the previous winter. The 8th and 10th Battalions were at Taranto from May 1918 to the Armistice working on the quays, a role that was of particular importance as it was through Taranto that all ammunition, clothing and food reached the British Forces in Salonika, Mesopotamia and Egypt. The presence of enemy submarines near Gibraltar prevented the colony from being an effective supply base for British forces

Commendations:

Second Lieutenant Dunlop of the 4th Battalion won the Regiment’s first Military Cross of the war for his actions on 7th November in extinguishing a burning ammunition dump. Second Lieutenant J.A.E.R. Daley of the 4th Battalion was acting as an observer in an aircraft during an aerial operation when the pilot was killed. He proceeded to climb into the front cockpit of the aircraft and, without having ever flown a plane before, successfully brought it back down and landed safely. Daley later transferred to the Royal Flying Corps and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, but unfortunately died in 1918. Captain Robertson of the 4th was awarded a Military Cross for his actions at the railhead on which the Battalion was working whilst supporting the Canadians during the operations at Vimy Ridge; he rescued wounded men and saved ammunition. On 2nd July 1918 enemy aircraft bombed La Bezeque Farm ammunition dump and it was only saved through the actions of Sergeant Miller (No.500), Sergeant McDonald (No.4136), Corporal Evans (No.5781) and Lance Corporal Cummings (No.14997) of the 3rd.

In October 1917 the 4th Battalion won a further eight Military Medals, thanks to the efforts of Sergeant Holland (No.3970), Company Quartermaster Sergeant Goater (No.19259), Private French (No.4368), Private Barton (No.4736), Private Davis (No.5777), Private De Pass (No.5766), Private Williams (No.8292) and Private Ferguson (No.6260). On one occasion, two of these men jumped on a cordite dump that was on fire and in the process of exploding. They pulled off the tarpaulin covering and helped to separate the burning ammunition and extinguish it. Several boxes exploded whilst they were on the stack and one man’s clothing was badly burned. Private Walker (No.7936) of the 7th Battalion won the Military Medal on 1st September 1917 for remaining behind on the top of a lit ammunition dump when all others had left; he rescued live rounds, with already ignited charges, from the centre of the dump and removed the adjoining boxes which had not exploded, despite having caught fire.

On 7th November 1917 an incendiary bomb was dropped on the Harengo ammunition dump near Boshinge. Private Thomas (No.10686) of the 7th Battalion noticed that the resultant fire was near to the boxes containing gas shells and high explosive shells and alerted the other men. He then proceeded to run to the dump to extinguish the flames and was quickly joined by Corporal Walker (No.10799), Lance Corporals Archer (No.9621) and Boyce (No.9741) and Private Smith (No.10619). Despite the heavy bombing of the area, they were successful in quelling the fire. For this Corporal Walker had a bar added to Military Medal he had received previously; the others received the award for the first time.

There are contradictory reports regarding the performance of the B.W.I.R. on the Western Front. The 4th were well regarded by the officers in charge of the ammunition dumps at Puckevillers where the West Indian soldiers “worked exceedingly well” and gave “every satisfaction”. Colonel Balfour, who was in charge of the 15th Labour Group, was very pleased with the manner in which they had unloaded ships at the Quai de France when they were stationed at Rouen. Sir William Manning, following a visit to the B.W.I.R. Battalions in France, made a speech in December 1917 to the Jamaican Legislative Council in which he recalled that an officer of the High Command had said to him, “I understand that there is some probability that the men may be moved from this area; if that is so, I do not know how I should get on without them”. In one instance, sixty men of the 6th Battalion unloaded a staggering 375 tons of ammunition in less than two hours. Reverend Ramson, the Padre of the 6th Battalion, later recalled how everyone who came into contact with the B.W.I.R. was always full of admiration for them and that officers of other labour companies, upon discovering his Regiment, always spoke very favourably of “those fine fellows from the West Indies”.

The work done by the West Indian labour battalions on the Western Front, while not sharing the perceived glamour of front line units, was still vital to the war effort and they performed hard, physical work in conditions no less dangerous than that of their comrades in the Middle East. Whilst there appears to have been some who resented this role, most seem to have embraced it. When some expressed concerns about the work allocated to the BWIR, this was often due to an expectation of front-line action, combined with the perception labour battalion duties were inferior or less important. On the whole the BWIR seems to have been held in high esteem. It is evident that the regiment performed well across all theatres of war in very dangerous and inhospitable conditions, often under shell fire, whether in support roles or in direct action.