The Middle Eastern Theatre

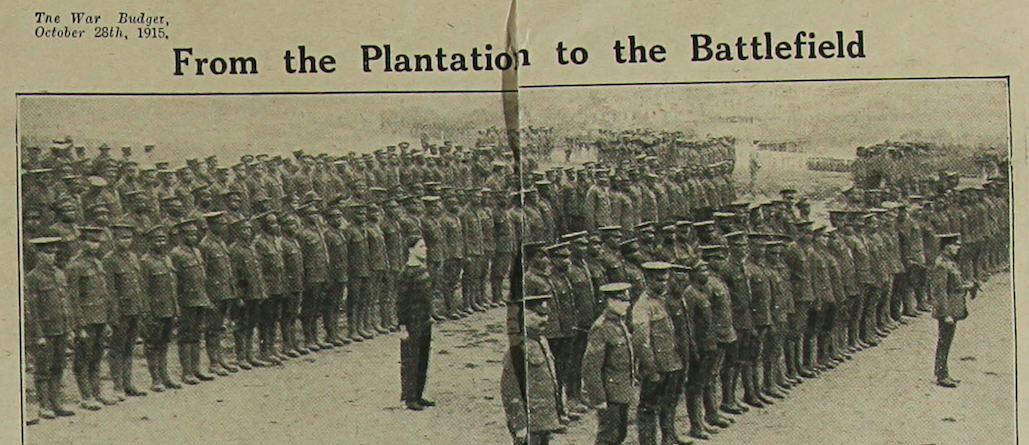

The Middle Eastern Front saw a very different style of warfare from the Western Front in Europe. The British forces in Egypt were originally known as the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force and the Force in Egypt but were amalgamated into the Egyptian Expeditionary Force on the 19th of March 1916 and consisted of British, Australian, New Zealand, Indian, West Indian and Egyptian Troops. The Egyptian Expeditionary force was originally led by General Sir Archibald Murray and from 1917 by General Sir Edward Allenby. Their primary foe was the Ottoman Empire, who was popularly referred to as ‘Johnny Turk’, with whom the British Empire had had an uneasy yet largely peaceful relationship within the region until the declaration of hostilities on 5th November 1914.

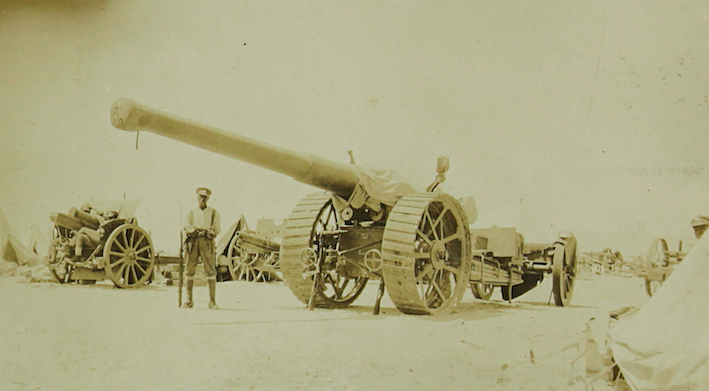

There were fewer troops in the Middle Eastern theatre than on the Western Front to the point that neither army had sufficient numbers to man large-scale static defences. Static defence was therefore, of necessity, limited to key points. There was therefore space not covered by intense machine gun and artillery fire in which troops could manoeuvre. Hence the use of mounted cavalry (both horse and camel) in this theatre and companies and other detachments were frequently deployed some distance from the main body of their battalion or regiment.

The other fundamental difference between the two was the lines of communication and transport. The lines of communication and supply were much shorter in Europe than in the Middle Eastern theatre. Thus, given the dearth of mechanical transport, particularly in the early years, the armies in the Middle Eastern theatre found it difficult to concentrate large quantities of men, material and munitions and were therefore less capable of mounting, among other things, the intense, sustained artillery barrages which became the norm on the Western Front.

There were, however, some similarities between the fronts: the combinations of trenches and barbed wire were used in both, as was the tactic of using artillery to break through the wire so as to allow access to the enemy positions. However, it is safe to say they were not such an obstacle for the more manoeuvrable troops in the Middle East as they were on the static Western Front. As mentioned above, the communications problems differed significantly between the two theatres. Germany had, as part of its basic battle plans, envisaged the strategic use of railways to serve the front. Moreover, the basic rail and road infrastructures on both sides on the Western Front were more developed than those in the Middle East. The lack of a developed road network meant that those railways that did exist in the Middle Eastern theatre were therefore very important. First Battalion were given assignments relating to trains, e.g. the construction of defences to protect the railway at Sheikh Zowaide or the building of a Decauville railway (a type of railway that was easy to construct, deconstruct and transport to wherever a railway may have been needed) under the guidance of the Royal Engineers. Some West Indian battalions were also present in Mesopotamia, modern day Iraq supporting the campaign there in similar duties.

The environment in the Middle East prevented trains being so widely used as they were in Europe, due to the impossibility of laying tracks on sand. The sand also caused other transport problems. As Lieutenant Colonel Wood Hill wrote in the First Battalion’s War Diary report from July 1917, the methods of transport provided to the First Battalion were useless on the heavy sands of the Sinai desert. As the soft desert sand could severely impede both the movement of light vehicles and infantry a ‘road’ of rabbit-netting could be laid out across the sand to assist with movement. Yet this was not an all-purpose cure for the problem as heavier loads could not be supported. Although other battalions and regiments were provided with camels to assist with carrying supplies and baggage, unfortunately the First Battalion were not provided with them which meant that most of the supplies and baggage had to be transported by rail during their early period in Egypt. For example, the reserve ammunition had to be carried by train rather than on the First Line transport with the men on march. This meant that each man only had one hundred and twenty rounds of ammunition each with no means to replenish them if they came under attack. The water tanks and the Field kitchens also had to be carried on the train, the former being especially important in the extreme heat.

The 1st Battalion War Diary indicates that whilst on march in the first half of 1917 they were able to access plentiful wells and pipelines along their routes (presumably because their routes had been reconnoitred to ensure such supplies). This was not however always the case and in mid-1917, through a period of intense training and marching, troops were placed on a maximum allowance of one gallon of water a day for all of a soldier’s needs, such as drinking, washing and cooking. This was in temperatures of up to 112 degrees Fahrenheit/ 44 Celsius. Eventually though many of the transportation problems were rectified and Lieutenant Colonel Wood Hill would claim that no Unit in Palestine had better transport than the British West Indies Regiment. At one point one of the battalions had 120 horses and mules and 36 camels attached to it. Following six weeks in the Jordan Valley in 1918, followed by a week of heavy marching and fighting in the hills of Moab the regimental transport returned to Jerusalem all fit and well, which was attributed to the fondness that the men had for these animals and the great care that they showed them. This was attributed to many of the men having learnt to handle animals such as mules from a young age on the plantations of the West Indies.

The different environment also resulted in a different set of problems for soldiers to face. Whilst troops on the Western Front had to deal with the problems caused by the cold and wet in Europe, such as trench foot as well as the sanitary conditions imposed by trench warfare. In the Middle East soldiers had to face the intense day time heat, cold nights and the difficulties with water supply. This meant that troops ran the risk of developing heat related issues during the day, such as sunstroke, issues relating to cold at night and without sufficient water they would suffer from dehydration. Whilst these issues were ever present in the Middle Eastern Campaign they could be exacerbated if troops had to take part in extended operations and thus have to move at speed via march in the intense heat with no opportunity to rest or refill their water bottles. Whilst soldiers on the Western Front could also catch a variety of debilitating illnesses those troops in the Middle East There suffered from the threat from some particularly virulent diseases such as Spanish Influenza, Malaria and Sand Fly Fever. Disease would prove to be the biggest killer of the soldiers of the British West Indies Regiment, an experience that was not unique during the war. In one small period, between December 1917 and January 1918, the issues they faced were more akin to those of the Western Front.

At the end of 1917 the 1st Battalion took part in the chase of enemy troops up into the mountains of Judea following the successful British assault on the Gaza-Beersheba line. The climate rapidly changed and they went from experiencing great heat to cold and rain up in the mountains. They had nothing to repel this save the summer clothing and single blanket they had carried in the Gaza-Beersheba operations, the quick motion meaning that they could not equip themselves with their winter clothing, greatcoats, extra blankets and bivouac sheets which remained at the railhead and could not be brought up due to lack of transport. The heavy rains also did significant damage to the roads, preventing transport by this means and the men had to deal with ankle deep mud. Over nienty-two men were admitted to hospital with bronchial infections. Despite this the men were noted to carry out their duties with great diligence and cheerfulness. The following January was little better, with the plains of Judea, to which they had come down to, described as being transformed in a mire of mud and water by heavy rains.

During a march between Gharbiyeh to Esud they had to proceed by a narrow track, no road, which the heavy rains had almost obliterated and covered with water and mud which made marching an entirely heavy arduous task with many of the men sinking over their waists into mud and water. In another incident the 1st Battalion’s transport vehicle became stuck in mud and could not finish it’s journey, resulting in the battalion having to spend a very unpleasant night with no shelter or covering from the heavy rains. Several men contracted pneumonia during this month, with seven dying as a result of exposure to the elements. They would face similar problems during the operations in the Jordan Valley with a lack of blankets and coats on the march to Es Salt, and many officers and men had to be evacuated to hospital suffering from the effects of exposure and also from an outbreak of Malaria.

Click here to read the War Diary of the First Battalion British West Indies Regiment.